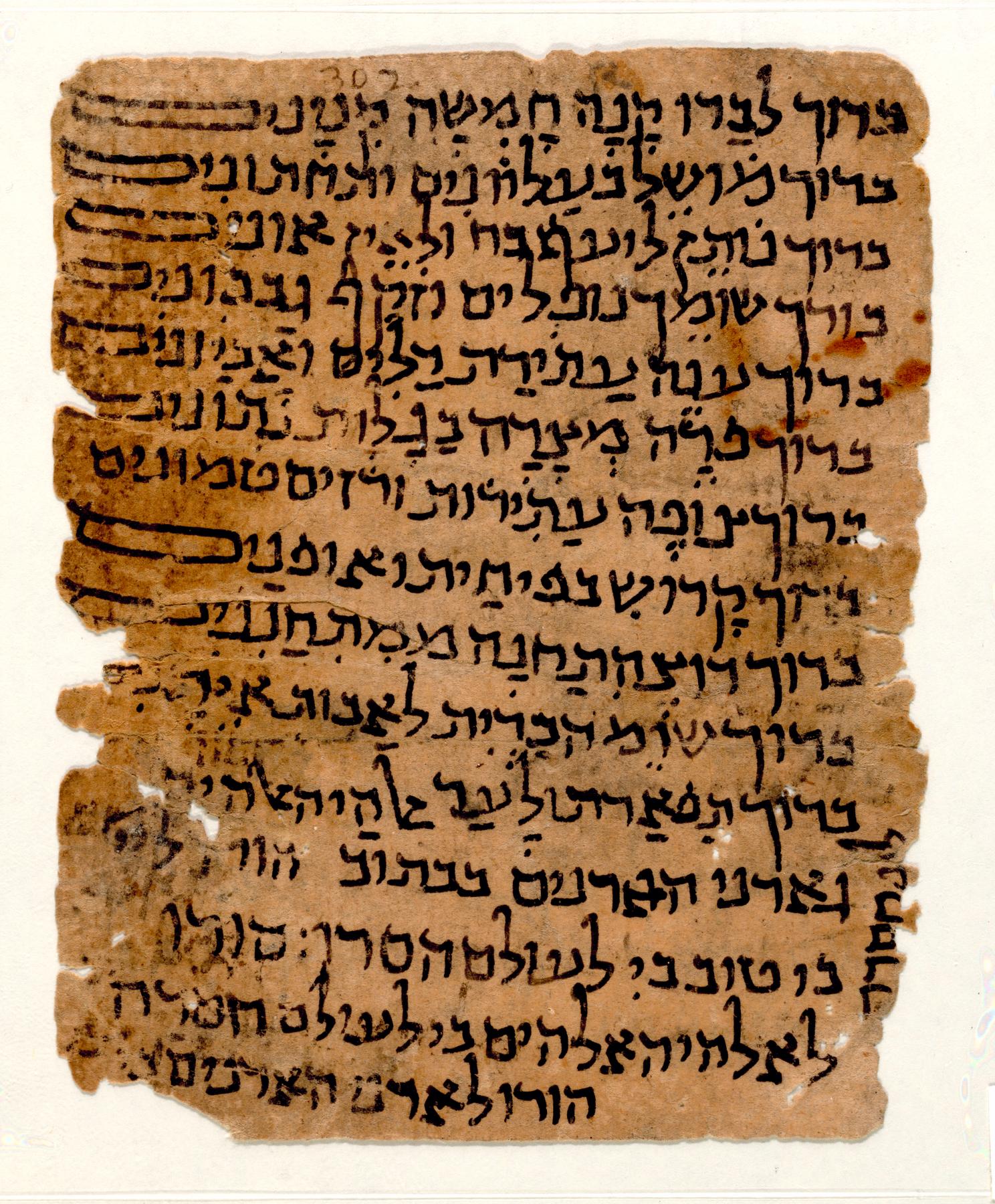

For nearly a thousand years, Jews at the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo stored their worn-out, torn, or otherwise unusable manuscript fragments — everything from biblical texts to business ledgers, Talmudic commentaries to children’s writing exercises — in the geniza, or storage room. During the nineteenth century, the archive was excavated by British academics as part of a surge of scholarly interest in the lives of the inhabitants of ancient Cairo. Now spread across dozens of repositories around the world, these more than 400,000 fragments help scholars piece together what life was like for these Jews and other inhabitants of the medieval Mediterranean world.

Scribes of the Cairo Geniza is an international collaboration led by Penn Libraries and the Zooniverse to annotate and transcribe these fascinating documents by harnessing the power of citizen science. Funded by an Institute of Museum and Library Services grant and celebrating its fourth anniversary this year, Scribes of the Cairo Geniza engages researchers and volunteers in public research to unpack how the people behind these fragments lived their lives. Ultimately, the project hopes to reconstruct how we think about the past.

Many of these fragments are damaged Torah scrolls or other texts regarded as sacred in the Jewish tradition. But we have also identified fragments of an everyday nature — marriage contracts detailing intimate family histories, advice from medical texts, and lists of food. Transcribing a few words on a page can tell us so much about the type of document! Even identifying key visual characteristics on a page, like a seal or a colon, gives researchers a head start in further investigating these fragments.

Take Part: Get Started With Scribes of the Cairo Geniza Today

Volunteers Studying History

To get started with the project, all volunteers need to do is choose one of our active workflows. Each workflow has a Tutorial and Field Guide providing information on how to get involved. Anyone can participate in the project, even if they have no knowledge of the Hebrew and Arabic language. Since 2017, over 9,500 volunteers have sorted more than 50,000 fragments into Hebrew and Arabic script, started discussions about what they’ve seen and learned and done the important work of transcribing ancient texts.

As the project manager, part of my job is helping volunteers explore what life was like for these Jews and other inhabitants of the medieval Mediterranean world. There’s a particular intimacy to exploring the Geniza: even without being able to read the text, volunteers are fascinated by the tangible evidence of past lives. The marginal doodles, wear and tear of parchment or binding of a manuscript connects volunteers to the physical objects, and reminds us that these pieces of paper are a very real connection to people, places and times past. Part of our goal is education and awareness to bring the public closer to the work involved in making digital collections like these accessible. We want people to understand the library processes of curation and preservation, the Geniza’s rich history and connection to Jewish communities, thought and tradition.

One of our most exciting discoveries was the Scribes of the Seder initiative, where volunteers and researchers worked together to create a patchwork Haggadah for Passover. The Haggadah, read at the beginning of Passover, details the rituals of the Seder feast and retells the story of the liberation of the Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt. Volunteers identified portions from various Haggadot in several languages, and our team ordered the fragments according to their place in the Seder. Collecting these fragments and displaying them together highlighted the ways in which traditions have changed over the centuries. Some that are today considered an essential element of a Seder were not so in the 10th century, such as the famous four questions asked by the youngest person present to begin the feast. But other traditions have remained nearly the same, such as singing at the end of the night.

Bright Future for Research

Ultimately, we hope Scribes of the Cairo Geniza will further scholarly research. And we know that’s already happening — our partners at Princeton hope to incorporate the data from Scribes into their database linking images, transcriptions, translations and research materials about the Geniza. Our team at the University of Haifa is using early data to compare the transcriptions to existing Jewish texts, speeding up the research process. Right now the project team is also exploring new ways to further break down research tasks, such as phrase finding and language identification.

Scribes of the Cairo Geniza harnesses the power of technology and the passion of the community to provide a resource of historical interest to anyone — professional historians, students and citizen scientists around the world. Working together to look at a fragment — whether we bring historical knowledge, language expertise or simply a new eye — the crowdsourcing community collaborates to learn more.