Last summer, my friend Henry Gargan became obsessed with birds. Everywhere I went with him — on a walk in the park, downtown or even driving in the car — became a birding expedition. The bird on the signpost had to be scoped out. That eerie call — a wood thrush or a hermit thrush? We had to listen and see. It was as if Henry’s very world had sprouted wings and begun to fledge.

What started as a casual distraction from Henry’s work became a full-on fixation. And he loved it. Being around him when his eyes lit up at a flash of brown feathers, you couldn’t help but love it too. But where did that interest come from?

According to Henry, it came from a mobile phone app called eBird. He downloaded the app last summer at first as a way to help identify birds he saw through his window while suffering through Zoom meeting after Zoom meeting during the COVID lockdown. At the time, he didn’t think much of it. But soon, Henry was quizzing himself on bird calls, proudly tacking new species to his “life list” and meeting eBirder friends out in the woods to find the first migrants of spring.

eBird is one of many citizen science projects that ask volunteers, including those without scientific backgrounds, to explore their world and gather observations. These projects are clearly having a profound impact on the lives of people like Henry. I’m part of a research team trying to understand that impact through a new citizen science project called SciQuest.

Connecting to Our Planet With Citizen Science

Henry’s life changed in a positive and fundamental way last year because of a citizen science project. That drastic transition raises some fascinating questions for me as a researcher studying the phenomenon of citizen science. For decades we’ve known that data shared with scientists by members of the public can be a tremendous boon to researchers. We know less about what citizen science does for the volunteers.

That’s why we started SciQuest, a citizen science project about citizen science. The goal of the project is to assess how exactly citizen science may be impacting the lives of people like Henry. What we’re finding out through SciQuest will help us make better decisions about the next steps for citizen science as it becomes a truly global phenomenon.

One of my main interests as a scientist is how our experiences shape the way we engage with environmental issues. For instance, we know that astronauts, upon seeing the Earth from outer space surrounded by a vast sea of black– a stark reminder that “there is no Planet B” — become dedicated to protecting that planet when they return home.

Might citizen science impact people in a similar way? After all, citizen science activities also encourage people to examine the Earth more closely — to step back from their daily lives and watch, measure, listen and record. But while few of us will ever get the chance to ride a space shuttle, citizen science can be done by just about anyone.

Some studies seem to suggest that citizen science is indeed having an effect on how participants interact with their world. For instance, joining biodiversity-focused projects like eBird or “The Big Butterfly Count” is linked to learning something new about wildlife, gaining a deeper appreciation for nature and getting more involved in conservation activities. But there’s still a lot left to learn about how significant these changes are for people, as well as how they might be occurring.

Take Part: Join SciQuest Today

Understanding the Why

Take Henry, for instance. What was it about his experience on eBird that turned birding from a weekend fad to a lifetime passion?

One hypothesis has to do with motivations. According to social science theory, the things we do are more meaningful for us if we’re “internally” motivated to do them. That means doing something because we think it’s fun or important — whether that’s reading a book or getting some exercise. Conversely, when we, say, go on a run just because a coach told us to or because we want to impress someone else, we’re unlikely to keep up the habit when that external pressure goes away.

So how do we help people develop internal motivations? Research shows that when three fundamental needs are met — when we feel competent, connected to other people and in control of our own decision-making — our motivations can shift from being “external” to “internal.”

That’s exactly what happened to Henry. After all, he started doing citizen science before he was all that interested in birds. Yet through eBird he had an opportunity to improve his bird identification skills, meet more experienced birders that were happy to share their knowledge with him and make his own decisions about how he wanted to explore the world of birds. In other words, Henry’s three fundamental needs were met. As a result, he transitioned from doing eBird because he was bored at work to doing it because he was truly passionate about birds.

But are these motivational shifts happening to citizen scientists besides Henry?

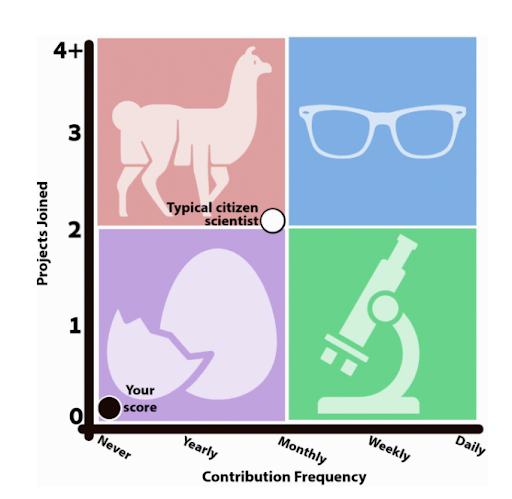

That’s where SciQuest comes in. SciQuest uses a series of quizzes to track people’s attitudes, knowledge, motivations and other things that might be impacted by their citizen science experience. Importantly, SciQuest measures both whether people are changing as well as how those changes might be occurring.

The project is designed to be an immersive experience that uses engaging quiz “modules” that participants complete a few times a year. In addition to helping us answer our research questions, these quizzes act as a resource for citizen scientists themselves to better understand and reflect on their experiences.

Rather than bombarding volunteers with a bubble sheet of questions, SciQuest uses videos, sliders and graphics, and allows participants to respond to fictional narratives. There are even fun, Buzzfeed-inspired quizzes to gauge participants’ knowledge of various subjects.

We pair responses to these quiz modules with data about the kinds of projects volunteers are joining, particularly on SciStarter. This will help us assess how combinations of projects, or certain kinds of projects, are connected to different outcomes.

We also plan to promote SciQuest to new audiences, such as volunteer groups with schools, churches and businesses that are trying citizen science for the first time. This will help us better understand the value of citizen science for new users, who might react differently to a project than more experienced users.

If we find that citizen science is indeed leading to some kind of change (i.e., an increased interest in the environment), it could inform how we make decisions about promoting citizen science to the public at large. Perhaps citizen science should be used in middle school science classrooms as a kind of hands-on learning. Or maybe it can decrease partisan divides between conservatives and liberals about collective problems like local habitat loss? These are questions that SciQuest is equipped to tackle.

Citizen science has certainly had a profound impact on my friend Henry. He spends more time outside than he used to. His knowledge of birds has gone through the roof. And he’s bonded in new ways with a whole community of people he had never interacted with before.

SciQuest is a way to quantify and understand that impact, multiplied among the millions of people that participate in projects every year. It is an attempt to document the downstream effects of making science a collective pursuit and a personalized journey.

Tackling global problems like climate change or the education gap requires novel solutions. Citizen science, a concept that’s both accessible and engaging, could play a role in solving some of those problems. SciQuest can help us assess that potential.

If you’re interested in joining SciQuest, head over to https://scistarter.org/SciQuest and complete the “Journey Prep” module. We’ll send you new quiz modules as they’re released. We especially encourage people to join the project who are just starting out in their citizen science journey, or who have never participated at all!